|

The History of St Edmund's Chapel The Consecration of the Chapel and the Death of St Richard by Rev T E Tanner St Richard's confessor, the Dominican priest, Ralph Bocking, in his Life of St Richard, published about 1270, wrote:

His face (indeed his whole body) lit up with joy, and he gladly agreed to their request. He went to the Chapel and solemnly consecrated it with great devotion. It is in these words that St Edmund's Chapel, Dover, comes into recorded history. The day was Laetare Sunday, 30th March 1253. It was the fulfillment of a wish that Richard had cherished for nine years. The people of Dover gathered around the Chapel and in his sermon (which was a model of brevity), St Richard left nothing unsaid in emphasizing the uniqueness of the occasion. He said: Dearly beloved: I ask you to bless and praise the Lord with me for allowing me to be present at this consecration, to his honour and to the honour of our beloved father, St Edmund. Ever since I was consecrated bishop, it has been my deepest wish - something I have prayed for with all my strength - that before my death I should consecrate at least one church to his memory. From the very depths of my heart, I thank God that he has not cheated me of my heart's desire. And now, brethren, I know that I am shortly to die and I commend my soul to your prayers. |

|

He finished mass, blessed the people, and went back to the Maison Dieu. He had fulfilled his last wish, preached his last sermon and said his last mass. |

|

John Capgrave (1393 - 1474), who edited an anonymous Life of St Richard, written some years before Bocking's, probably in connection with the canonization of St Richard, tells of the next few days: On the day following the dedication, weak from his many labours and sickness, and not realising at his usual hour of rising that his strength was leaving him, he went to chapel and began to sing the divine office. When, however, he stood up to say mass, his limbs could no longer support him. He fell fainting to the ground. His friends carried him in their arms and laid him on his bed. He told William, his Chaplain, that he would not recover from this illness, and ordered him to prepare carefully everything that was necessary for his funeral, lest his 'familia' should be worried about the arrangements. He told Simon of Tarring the day on which he would die. He asked that a crucifix should be brought to him, and with great devotion he kissed the places of the sacred wounds; and he began to caress it very gently, as if he saw our Saviour in the very act of dying, and he said: 'I give thanks to you, Lord Jesus Christ, for all the benefits which you have given me, for all the pains and insults which you have borne for me: on account of which this sad lament escaped your lips "There is no sorrow like unto my sorrow". You, Lord, know that if you wanted, I would suffer all manner of insults and torture, and death itself for you, and since you know that this is true, have mercy on me because I commend my soul to you.; He frequently repeated the words of the psalmist: 'Into your hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit'. And turning to Our Lady, both in his heart and on his lips, he said: 'Mary, mother of grace, mother of mercy, protect us against our enemy, and receive us at the hour of our death'. He told his Chaplains not to cease repeating these words in his ear. As he prayed, surrounded by priests, religious, clerics and the faithful laymen, the blessed Richard gave back his soul to his Creator. He departed this world about the fifty-sixth year of his life, and the ninth year of his pontificate: on the third day of April, at midnight. His body, which had endured so many vigils and been broken by the hard earth on which he had so often lain, was emaciated by his fasts and frail on account of his austerities, but after his death it was radiant and glowed with an unnatural light. Ralph Bocking, in his fuller account of Richard's death, gives more details about his foretelling of the actual day of his death. Simon of Tarring, faithful as always, was close to his bed, and as Richard grew weak, he said: 'My Lord, the celebration of Our Lord's Passion is close at hand, and as you have been a sharer in his sufferings, by his grace you will be a sharer in his joy'. The saint smiled and, applying to himself the words of the psalmist, said: 'I was glad when they said to me "We will go into the house of the Lord",' and turning to Simon, he said: I will share in the great feast'. In many accounts of St Richard's death it is written that he died on Good Friday, 3rd April 1253. Some writers add the flourish that he died at 3 p.m., repeating the words: 'Into thy hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit'. The chronology of his last week, however, was: Sunday .... March 30th. Mid-Lent Sunday: consecrated St Edmund's Chapel. This is confirmed by Ralph Bocking, who proves himself a reliable witness, and by reference to the calendar of 1253. Good Friday that year was on 18th April. In his last days Richard concentrated solely on dying. When a doctor was called and wanted to take specimens he said: 'What on earth is the use of making further examination of my body when death his already at the door. It is clear that I am shortly to leave this body behind me, and what matters now is that I should think about the Lord.' As Bocking commented: 'He seemed to put away all the concern a Marthe has for many things. He wanted only one thing - what Mary was praised for because she had chosen it above everything else.' After Richard's death, and especially after his canonisation (January 1262), St Edmund Chapel, as well as being the Chapel for the Cemetery of the Poor, was a place of pilgrimage.

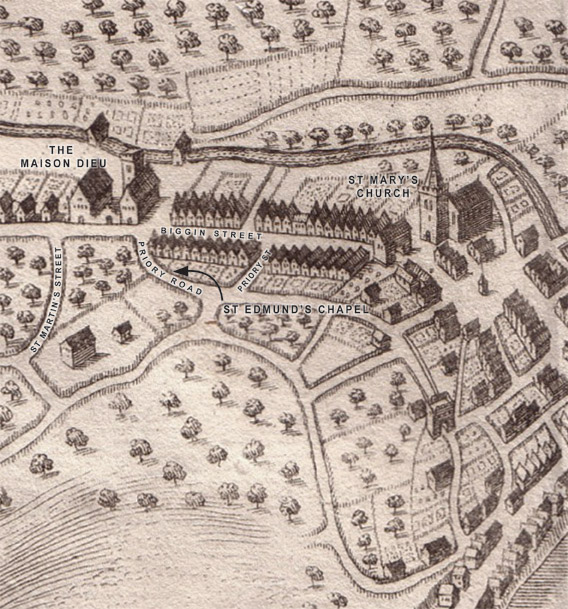

Many people living in Dover today can tell you of bones and chalk tombs found in the ground, close to St Edmund's Chapel. It has always been so. Mr Bavington Jone' transpcript of Hammond MSS., p. 22 (drawer No. 214, in the Court Room, Maison Dieu, Dover), reads: 'St Edmund's Chapel is now - A.D. 1764 - to be seen entire, and a vast number of human bones have lately been discovered near it'. And C. R. Haines (Dover Priory, 1930, p. 150) tells of a rather gruesome event. The floor of the Cornet Inn, which stood in Priory Road immediately south of the Chapel, fell in and a vault was discovered, containing chalk coffins placed on shelves. Mr Barnes, the proprietor of the Cornet Inn, kept one of the skulls and it was still on the mantelpiece when his widow died in 1891.

It is, however, as a thirteenth-century Pilgrimage Chapel that St Edmund's has most interest. In the floor beside the altar, there is a small cist (pronounced 'kist;) which is almost without doubt the spot where the bowels of St Richard were buried.

To us in the twentieth century the mention of bowels has rather unpleasant associations, but in the thirteenth century people were not so squeamish, or perhaps they were more biblical. 'Bowels' in the Bible is associated with mercy, and in particular, with God's mercy towards man (Ps, xxiv, 6; Luke i, 78; I John iii, 17 - among many that could be quoted). It was a common medieval practice to 'Eviscerate' a dead person to slow down the process of corruption when there was a time-lapse between death and burial. Besides Ralph Bocking, with Richard when he died was another friend - Simon, Vicar of Tarring (near Worthing), who had taken him in when Henry III threatened with dire penalties anyone who fed or housed him. These two men presided over the arrangements for Richard's burial. That the disembowelling was not just a practical precaution to prevent too-rapid decomposition is amply testified by what Ralph Bocking wrote in his Life of St Richard: Before his death, Richard had willed that his body should be buried in his Cathedral Church at Chichester, which is quite a long way from the place where he died. I think, therefore, that it was not so much by human design as by divine providence that he, who during his life had never shut the bowels of his mercy to the needs of the poor, should, in his death, give the bowels of his body to the poor. So it was that when his bowels were taken from his body, they were reverently buried in the Chapel of the Cemetery of the Poor, which just previously he had dedicated to the honour of St Edmund, the Confessor. Can anyone doubt that this was not well done? His very bowels preserved the memory of St Edmund. For his words and his last will and testament prove that he loved Edmund to the innermost depths of his being. |

|

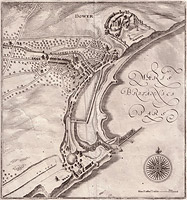

At the spot where his bowels were buried, many favours where granted to those who prayed 'through the bowels of the divine mercy and by the merits of St Richard'. When the Chapel was being restored, it was considered possible that the 'bowels of St Richard' had been placed in an urn or wooden box or leather bag since it was obvious that Ralph Bocking had considered them a precious relic. It was decided therefore, to invite a team led by Brian Philp, the well-known Kent archaeologist, to excavate the inside area of the Chapel. Many of the results appear elsewhere on this website but recorded here in some detail are those those which concern the relics of St Richard. A priori, it was considered probable that the relic would have been buried near the altar. It was also thought that the altar would have been at the east end of the Chapel. The first excavation was, therefore, at the east end. This revealed a lot about the history of the Chapel, but although the dig went back, through the Roman level, to the undisturbed 'natural' level of the earth, no sign was found of anything to suggest thirteenth-century burial. The finds of this trial excavation were so interesting that the next days were taken up with further excavations to confirm and enlarge its findings. The base of the altar had now been located in the eastern half of the Chapel, more towards the middle than the eastern end. It was only on the last day of the dig that excavations were made near the altar base. These revealed a small cist to the south side of the altar. The original 'hole' had been some thirty-four inches long, and some twenty-two inches wide. It had been dug into the earth without any dressing. The base was earth. The sides had then been roughly plastered with puddled chalk. this had simply been hand-pressed round the sides of the hole, about three inches thick. The resulting cavity had been filled in with loose earth from the thirteenth-century layer of the Chapel's soil, and covered with a layer of chalk and mortar. What led to the discovery of this cist was a round hole, three inches in diameter, at a very, very slight angle, inclining to the altar. This hole was found to be eleven inches in depth. Undoubtedly a wooden stake had originally been place in the loose earth of the cist and protruded out of the cist and touched the altar. The stake had rotted away. The cist was partially sealed by the base of the altar. It was very probably of thirteenth-century origin. It was certainly constructed to bury something. That 'thing' was important enough to merit a stake to indicate its exact position. Its position, at the base of the altar, indicates both the importance and the sacredness of what was buried. No mason was responsible for such a poor construction, which could suggest haste, consistent with a death and disembowelling. Read again what the eye-witness, Ralph Bocking, wrote: 'At this spot many favours were granted', and there seems no reasonable doubt that this is the spot where the bowels of St Richard were buried. No trace of an urn, a wooden box, or a leather bag was found. The slab of chalk and mortar which had covered the cist had prevented the loose earth inside from being subjected to any downward pressure, and when uncovered it was still remarkably loose. Had there been a container which in the course of time had rotted away, there would have been some settlement in this loose earth. The indications are, therefore, that this cist was prepared on the orders of Ralph Bocking and Simon of Tarring: that St Richard's bowels were reverently ('venerabiliter') deposited in it and covered with loose earth and that the cavity was then slabbed over. The question can be asked whether the stake was intended only 'to indicate the spot'? Ralph Bocking continues: As soon as his body, robed in his episcopal vestments, had been put in its coffin, a great crowd of people came from everywhere, to be present at the funeral of a man worthy of such veneration. That man was counted lucky who touched the coffin, or even the hem of the vestments, or who could touch with a ring or other ornament his face, hands, or feet. Whatever had touched the saint was considered to have been made holy and was kept as a relic. It would not have been extraordinary in the middle ages if this stake had been a way of 'touching the saint', on the principle that what you do by another, you yourself do. Strangely, there is corroboratory evidence that in the case of St Edmund that the Chapel where the bowels were buried was not without significance. St Edmund died at Soisy on 16th November 1240, and, as his body was to be taken to Pontigny to be buried, he, too, was eviscerated. Doctor C. H. Lawerence, in his Life of St Edmund (Oxford University Press, 1960, pp. 14 and 15), writes: After the body had been embalmed, therefore, the clerks set off with the remains of their archbishop. The procession met with impressive demonstrations of popular devotion all along the route. At the village of Trainel enthusiasm became so intense that the abbot of Pontigny began to fear for the safety of his precious freight and decided to take a strong line with the thaumaturge. The saint was invoked and ordered in virtue of obedience (he was a confrater of Pontigny) to desist from his miracles until the procession reached home. Thereafter progress was better. In these propitious circumstances no time was lost in petitioning for a papal commission of inquiry. The earliest dated letter of postulation was dispatched in December 1240, by the abbot of Provins where St Edmund's entrails were buried. It was the abbot of Provins, where his bowels were buried, who initiated the process of Canonization a month after Edmund's death, though 'the main initiative came from Pontigny'. The Dissolution and the Re-discovery of the Chapel Presumably, St Edmund's Chapel was still a place of pilgrimage at the time of the Reformation. In 1534, the Master and Brethren took the oath in support of royal supremacy, as required of them by the King's commissioners. The monasteries and friaries were all dissolved by 1540, but hospitals, such as the Maison Dieu, were left for more piecemeal treatment. Possibly the Maison Dieu, like the Hospitals for Poor Priests and Eastbridge at Canterbury, would have continued to serve its various charitable purposes into Elizabethan times if, on the completion of the King's new harbour works, covetous eyes had not turned upon it. On his way to Calais in June 1544, Sir John Russell, Lord Privy Seal, reported from Dover to the King's Council that there was great need of a victualling yard there for the King's armed forces. He suggested that the appropriation of the buildings of the Maison Dieu for that purpose would be 'the godliest act ever King made these thousand years within the realm'. On 11th December 1544, the Master and Brethren duly signed the surrender of the Maison Dieu, St Edmund's Chapel and all its other property to King Henry VIII. There is an obvious link between the surrender of the Maison Dieu with St Edmund's Chapel and the building of Dover Harbour. Both John Thomson, who was the Master of the Mason Dieu at the time of the surrender, and John Clerke, who was Master at the time of the taking of the oath of supremacy, were surveyors of the building of the Harbour. Antony Aucher, who was with Sir John Russell, in a letter to Cromwell describes Thomson as 'covetous and knowing nothing of what he was doing; he began this labour without experience, but even as a blind man casts his staff; and so hath builded until this day, thinking he hath done well, and is clean deceived'. Nevertheless, Thomson (who, incidentally, was also Vicar of St James' Church) was appointed Overseer of the King's water workes at Dover in January 1541 - perhaps in return for having made over to the King for the building of Sandgate Castle 526 pounds of iron from the Maison Dieu, and for having prompted the suggestion that the Maison Dieu, with St Edmund's Chapel, should be taken over as a brew-house, bake-house, and other offices. Apparently, he was not very successful as a surveyor at Dover Harbour. Several times he wrote to Cromwell, when mishap followed mishap, explaining that as he had been poisoned he had not been able to overseer the work properly, or that the weather had been atrocious. The exact use to which the Chapel was put at this period is not known. In the course of the centuries buildings were built and re-built to its north, south, east and west. At times, these buildings abutted the Chapel itself. It was so hemmed in that it was lost to view and forgotten. Even when it was re-discovered, it was at first thought to be St John the Baptist's Church which, before the Reformation, stood 'by the Maison Dieu'. The re-discovery of the Chapel is of such interest that we make no apology for quoting in full a paper read by Mr E. P. Loftus Brock, F.S.A. Honorary Secretary of the British Archaeological Association, published in the Association's Journal, Volume, XL (1884, pp.229-30) It will be within the memory of many now present, that during the recent Congress at Dover (August 1883) we had an interesting paper on the old churches of the town by the Rev. Canon Scott-Robertson. At its close a discussion ensued, in the course of which Edward Knocker, Esq., F.S.A. said he had heard of the existence of some ancient masonry behind the houses and shops in Biggin Street, not far from the Maison Dieu which belonged possibly to one or another of the churches, the sites of which he considered were not ascertained. This may have been learned by Mr Knocker from a resident of Pencester Street. Rev T Tanner made it a part of his duty to this association to survey the spot prior to his leaving the town, and subsequently reporting the result.

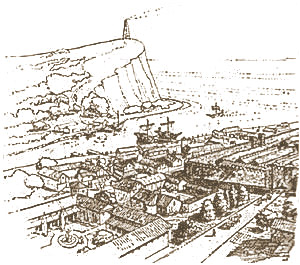

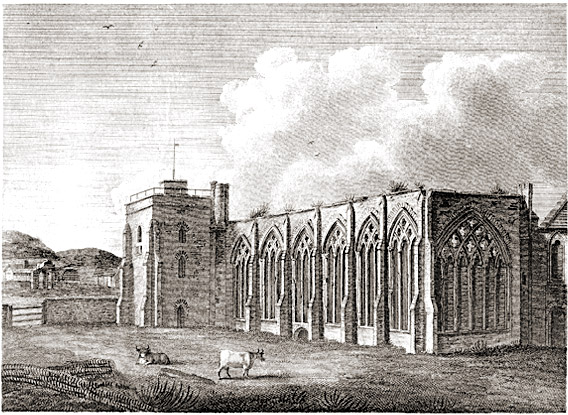

There is more to be traced than some mere masses of masonry. There is a small building all but perfect. The walls are intact, except that they have been cut into and altered: and the original roof covered with tiles, remains. It is a small chapel built east and west, and measuring 28 feet in length by 14 feet in breadth. The walls are of rubble masonry, 2 feet thick, having quoins and dressings of Caen stone. There is a plain pointed western doorway of two orders, having roll-mouldings. There has been a small lancet window in the gables once, of which the jambs still remain. Two simple, lancet-headed windows, widely splayed, have given light in the north and south aisles alike; and the east end has had, apparently, a couple of similar windows. There are no buttresses and no ornamental portions, if we except a moulded string-course which has existed internally below the sills of the windows. It can be traced at intervals here and there, in mutilated condition. The roof is of fairly high pitch, and it has had tie-beams, collars and strutts; the former having only recently been sawn through and removed when the upper part of the roof was filled up for storage purposes, lining it with match-boarding and inserting sky-lights. the present use is entirely for trade purposes. A blacksmith has the east end. Doors are broken through the walls, a fireplace erected, a division-wall inserted, new windows, and a floor over the whole. The building is hemmed in by either the backs of the shops in Biggin Street, or by the newly-built shops in Priory Road, from which the blacksmith has a narrow approach to his workshop. The chapel, therefore, as a whole cannot be seen at once, and its exterior can only be made out piecemeal from the various surrounding buildings (p. 230). It is, therefore, not at all remarkable that its existence has not been hitherto generally known. The south side is quite hidden, and it is a matter of some difficulty now to realize that this was once a detached building in full view of every passer-by. The position must have been a conspicuous one, standing at the entry of the town, at its northern of principal approach, and close under, and outside, the boundary-wall of the great Priory of St Martin's, which was on the opposite side of Priory Road. The details of the simple architecture show clearly that the date is of the end of the twelfth century or the beginning of the thirteenth. It had been one of the once numerous wayside-chapels, but whether or not belonging to St. Martin's Priory, probably future observations may determine. Although of such moderate dimensions its existence is worthy of record, not only as a matter of local interest, but as an example of a class of buildings of which we possess few examples. The Chapel must have passed out of living memory shortly before Mr Loftus Brock visited it, for in the Abstract of Title deeds in 1840 it is described as 'Ancient Chapel', but in the Abstract of 1887 as a 'Store'. It does not seem to have been identified as St Edmund's Chapel until some years later. The Reverend T. S. Frampton, F.S.A. first mentions it by its right dedication in an article, 'St Richard at Dover', in St Mary's (Dover) Parish Magazine, in July 1909. and Mr Arthur Hussey gave it wider circulation in a series of notes on 'Chapels in Kent' (Archaeologia Cantiana, Vol XXIX, 1911. p.234).

|

|